Planning Permission vs Permitted Development Rights: A Practical UK Guide

By Manzil Studio Ltd- 7 min read

If you are dreaming of extending your home, converting a loft or re-purposing an existing space, you will soon encounter two key terms: planning permission and permitted development rights. Knowing the difference and when each applies can save you time, money and a great deal of frustration. This guide explains both concepts and offers practical advice to help you move forward with confidence.

What Is Planning Permission?

Planning permission often referred to simply as “planning” is formal consent issued by your local planning authority (LPA). Its purpose is to ensure that your project is acceptable in terms of its effect on neighbours, the character of the street, local wildlife, drainage and other key planning considerations.

You normally need planning permission for significant alterations to a property or any change in its use. Typical examples include large extensions, the addition of a new outbuilding or turning a home into business premises. To obtain permission, you submit a detailed planning application with drawings, site plans, a design and access statement and, where required, an environmental impact assessment. Your neighbours are then invited to comment during a public consultation period. The LPA weighs the proposal against national and local policies before deciding to grant or refuse permission. If consent is given it is often subject to conditions; if it is refused you can appeal or revise the plans and re-apply.

Understanding Permitted Development Rights

Permitted development rights, often abbreviated to PD rights, are automatic rights granted by the government that allow certain building works to be carried out without a full planning application. They exist to make routine home improvements simpler and quicker.

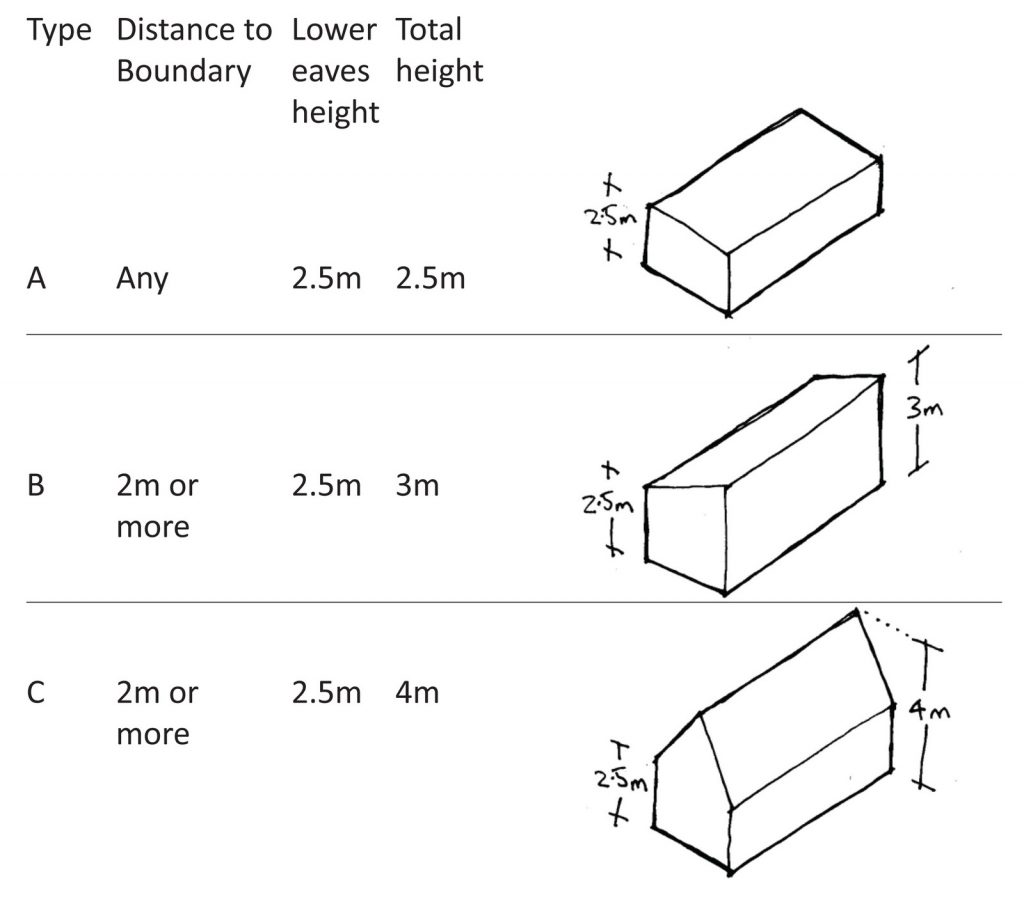

These rights, however, are subject to strict limits on height, size, location and materials. Some projects such as larger rear extensions or particular roof alterations require you to notify the council and obtain prior approval. This is not as involved as a full application, but it allows the local authority to check issues such as flood risk, contamination, noise or impact on highways before you begin.

PD rights are not absolute. They can be restricted or removed through an Article 4 Direction or by national rules, particularly in conservation areas or for listed buildings. And, even if your project qualifies as permitted development, you must still comply with building regulations, which govern structural safety, insulation and fire protection.

Typical Projects Covered by PD

Many common improvements fall within permitted development. A modest rear extension that remains within defined size and height limits is often possible, sometimes with prior approval. Loft conversions can also qualify, provided they remain within the permitted volume and do not raise the roof height. In some cases, converting an outbuilding or garage is allowed, and minor works such as replacing windows, adding cladding or building a conservatory can also be included.

That said, work to the front of a property or any alteration to a listed building is far more likely to require full planning permission.

When Planning Permission Is Required

Planning permission remains essential in a number of situations. Large or multi-storey extensions, or any alteration that significantly changes the footprint, height or overall appearance of a property, almost always require it. A change of use such as turning a dwelling into a business will need consent, particularly where parking, access or traffic might be affected.

Properties in conservation areas or near listed buildings are subject to tighter controls, so even works normally covered by PD may need formal permission. Listed buildings themselves almost always require listed building consent for any work that affects their special architectural or historic character. Full planning permission is also usually needed for the demolition and rebuilding of a significant structure.

When PD Rights Require Prior Approval

Some projects are technically permitted development but still need the council’s prior approval before work can begin. Larger rear extensions or certain outbuildings, for example, require the LPA to check matters such as highways impact, noise, contamination or flood risk. Loft conversions may also need prior approval in sensitive areas, particularly where they could affect the external appearance of the property. If the authority raises concerns, you may have to amend your plans or apply for full planning permission instead.

The Decision Process

For a full planning application you submit detailed drawings, site plans and supporting statements. The LPA assesses your proposal against national and local planning policies and then issues a decision granting or refusing consent, often with conditions attached.

The prior approval route, by contrast, is a lighter process. You submit only the information required for the specific concerns the council must check. If the authority is satisfied you can proceed without a full planning application.

Costs and Timescales

A full planning application usually takes several weeks to a few months, depending on complexity and whether neighbours raise objections. Application fees vary according to the type and scale of the project, and you may also incur costs for surveys, design work and specialist reports.

Permitted development projects generally involve lower upfront costs and can progress more quickly, though you will still need accurate drawings and sometimes pre-application advice. Prior approval is typically faster than a full application, but if it is refused or PD rights have been removed locally you may still need to apply for planning permission.

Practical Advice for Homeowners

Before you invest in detailed designs, contact your local planning authority for a pre-application check. This will confirm whether permitted development rights apply to your property and whether any local restrictions such as conservation area controls are in place.

Make sure you understand the specific constraints on your home. Check whether it is in a conservation area, is a listed building or is subject to restrictive covenants. Consider the design and its impact: think about materials, height, neighbour amenity, access, parking, drainage and flood risk.

It is usually wise to engage a professional architect or planning consultant who can prepare accurate drawings and guide you through the planning or prior-approval process. And remember, keeping neighbours informed from the outset helps reduce objections and potential delays.

Case Studies

Consider a semi-detached house with a modest rear garden. A two-storey rear extension remains within the size and height limits set out for permitted development. The homeowner applies for prior approval to check for issues such as contamination. The council raises no concerns and the project proceeds without full planning permission, subject to building regulations and the conditions of prior approval.

Now imagine a loft conversion in a conservation area. In most locations this would be covered by permitted development rights, but in a conservation area those rights may have been restricted. Here, the homeowner must prepare a full planning application and pay close attention to materials, roof alterations and the impact on the street scene.

Finally, take a listed building. Any external alteration or structural change will almost certainly require both listed building consent and planning permission. Permitted development rights are minimal, so specialist advice is essential and you should plan for longer timescales and higher costs.

Final Thoughts

Navigating planning permission and permitted development rights can feel like negotiating a maze. The key is to start with a clear understanding of what you want to achieve, assess the constraints of your property and location and involve the right professionals early. A careful, well-informed approach will save time and money and give your home-improvement project the best chance of running smoothly from first sketch to final build.